- Home

- Hugh Ambrose

Liberated Spirits

Liberated Spirits Read online

BERKLEY

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014

Copyright © 2018 by Ambrose, Inc.

Penguin Random House supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for every reader.

BERKLEY is a registered trademark and the B colophon is a trademark of Penguin Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Ambrose, Hugh, author. | Schuttler, John, author.

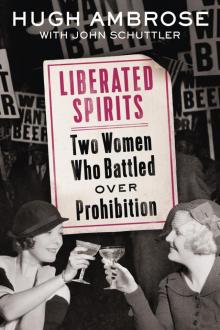

Title: Liberated spirits: two women who battled over Prohibition/Hugh Ambrose, with John Schuttler.

Description: First edition. | New York: Berkley, [2018]

Identifiers: LCCN 2017052487 | ISBN 9780451414649 | ISBN 9780698183636 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Willebrandt, Mabel Walker, 1889–1963. | Davis, Dwight, Mrs., 1887–1955. | Prohibition—United States. | Women—Political activity—United States—History—20th century. | United States—History—1919–1933.

Classification: LCC HV5089.A576 2018 | DDC 344.7305/41—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017052487

First Edition: October 2018

Jacket photos: image of women courtesy of Old Visuals/Alamy Stock Photo; background image of demonstrators courtesy of Sueddeutsche Zeitung Photo/Alamy Stock Photo

Jacket design by Emily Osborne and Colleen Reinhart

While the authors have made every effort to provide accurate telephone numbers, Internet addresses and other contact information at the time of publication, neither the publisher nor the authors assume any responsibility for errors, or for changes that occur after publication. Further, publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

Version_1

For Ande, Elsie, and Brody

For ever

Contents

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Introduction

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Acknowledgments

Postscript

Bibliography

A Note on Sources

Endnotes

Index

About the Authors

Introduction

The rumrunner* got word on Sunday evening that his ship would soon come in. Roy Olmstead*; his business partner, Tom Clark; and nine others drove north out of Seattle as the evening darkness settled, their convoy of eight cars driving fifteen miles on the Edmonds-Seattle paved highway to the rendezvous point, a dock jutting fifty feet into Browns Bay of Puget Sound near a small, little-used station on the Great Northern Railway called Meadowdale. Roy and Tom had both learned the art of bootlegging while working their “day jobs.” In 1914, the citizens of Washington State had voted to outlaw the manufacture and sale, but not the consumption, of alcohol, and put the onus of enforcing the statute on their state and local police departments, such as the Seattle Police Department, which employed both Roy Olmstead and Thomas Clark. By the time national Prohibition went into effect, Seattle’s cops had watched the inhabitants adapt for almost six years, finding ways to enjoy alcohol on a regular basis, their desires translating into handsome profits for the moonshiners who distilled alcohol and the rumrunners who imported it. While Olmstead never revealed when he got into liquor smuggling, his ability to secure probation rather than jail time for many criminals drew the gratitude of those willing to pay for his influence, his naked ambition following the quickest path to wealth. His ethics already compromised, Olmstead “saw no crime in buying and selling booze,” and was unable to reconcile the law’s allowance for consumption while forbidding a supply.1 He had watched two rival gangs devoted to “rum-running” slowly destroy each other through years of warfare, leaving an open playing field even as the federal government began to enforce the ban on liquor.2 The demand for good liquor, Lieutenant Olmstead knew, would continue to seek new sources; the way to profit from it was to import the best brands from Canada, a little more than a hundred miles to the north: a country where Scotch, gin, vodka, champagne, wine, beer, and so much more were still legally sold, purchased, exported, and consumed. Any boat could take on a load of good Canadian whiskey and steam away, so long as the export duties to Canadian customs had been paid. Islands great and small littered Puget Sound, the grand waterway connecting Seattle with two of Canada’s bustling cities, Victoria and Vancouver, offering smugglers a more-than-sporting chance to evade the mere two U.S. Coast Guard ships patrolling the waters. Back in Seattle, bottles bearing brand names commanded almost double the price that Roy Olmstead paid for them, creating the opportunity for extraordinary profits, a river of income that made his new career irresistible. The intelligence, initiative, and competence cited by his superiors as reasons for his rise in the police department served him equally well in his new profession.3 Roy Olmstead had the key assets to succeed: a talent for inspiring confidence in business partners for a venture in which no contract or agreement carried the force of law; the ability to manage an organization, a skill cultivated in his years rising through the ranks of the police force; and all the pluck and entrepreneurship of a born capitalist. This March evening found Olmstead and his associates exercising all their talents to bring in a large shipment of choice liquors and wines.

Just after one o’clock on Monday morning, the bootleggers turned left, off the paved road, and drove down the steep hill to the water. Their cars—rear seats removed to make room for the bottles, the cargo space supported by heavy-duty springs, the cars’ engines tuned for maximum power—could not fit into the narrow roadway near the dock, so they stopped in a line and waited. Olmstead had one of his men begin flashing a light periodically, facing westward out into Puget Sound. In less than an hour, the engines of the Jervis Island could be heard approaching. With enough cargo space to convey nearly eleven hundred cases from Victoria, Canada, across the Strait of Juan de Fuca, and down Puget Sound, Roy’s wooden-hulled boat had not been crafted for speed—it couldn’t even make ten knots—but her stout frame handled the job in workmanlike fashion. As soon as she was tied to the pier, the unloading began.

Roy and Tom watched as their foreman, waving an electric flashlight and hollering profusely, directed the process of toting the cases from the boat and up to the waiting cars, sending each loaded automobile on its way and waving in the next. Satisfied with the arrangements, his own car loaded, Roy drove away up the hill, only to find a barricade of logs at the apex. Men brandishing guns—thieves or cops, he did not know—ordered him to stop. As they neared his car, Roy spotted a way around and gunned the engine. Shots from their pistols did the men no good as he swerved back onto the dirt road, eventually picking up the pavement and heading south at full speed, surely wondering whether the gunmen were stealing his l

iquor or arresting his men, who had been instructed simply to turn over the goods if waylaid by hijackers. If the ambushers proved to be revenuers (agents of the federal Internal Revenue Bureau*), or former revenuers recruited to be members of the brand-new Prohibition Unit, he had a different set of problems. In more than a century of chasing down moonshiners and others not in compliance with government liquor-tax policy, revenuers had built a reputation for unpredictability, some being virulent Prohibitionists smashing stills and bottles, others willing to take a bribe to turn a blind eye. It was unclear how they would handle their new job, enforcing the federal Prohibition law, any change in their tactics imperceptible since the law had gone into effect two months earlier. What exactly would happen to those arrested and what would be the long-term effects of this new force on his operation were serious questions for Olmstead.

Roy had been at home a few hours when the phone rang just after six a.m., his captain announcing that he knew all about the bust, as did the sheriff’s office in Snohomish County, where the raid had taken place. The revenuers had recognized Lieutenant Roy Olm- stead, a well-known rising star in the Seattle Police Department, and had arrested Sergeant Tom Clark and seven others at the scene. The police car arrived at Olmstead’s house minutes later, one of Olmstead’s own patrolmen at the wheel, to take him down to the station. Olmstead told the officer the same thing he would later tell the police chief: he had been excused from his regular shift to care for his sick wife and daughter, knew nothing of the “liquor deal,” and stood ready to face his accusers.4

The chief did not believe Roy, or Tom Clark, who claimed he had gone to the dock to arrest the bootleggers. Chief Warren fired them both summarily, sending Roy to the county jail to await further questioning and a statement of charges, while Clark, who had been arrested by federal agents, was jailed at the federal immigration detention station, no federal lockup being available.

The newspapers’ evening editions spread the news across Seattle. In recent weeks, several landings of liquor had taken place at the Meadowdale dock, alarming the station agent for the railroad, a concerned citizen who had gotten in touch with Donald A. MacDonald, State Director of the new Prohibition Unit. MacDonald had been pleased to get the tip, eager to shift focus from arrests of peddlers of a few bottles to the rumrunner of several hundred.5 Olmstead may have counted on the inexperience of the Prohibition Unit, but not on its luck. MacDonald’s agents had almost missed the bust, three of them stumbling in the darkness, nearly shooting one another. “As fast as the cars were loaded with liquor and came up the hill we’d stop them, line the men up alongside the road and drive the car out of sight and gather in the next one,” exclaimed the son of the railroad station agent. After they secured the cars, they went down the hill and tried to take the delivery boat. The boat captain could be heard trying to start its motors. The railroad agent fired repeatedly into its wooden hull before the engines caught and the hulking shape pulled away. Though the dark had prevented a good look at the boat, the agents thought the Coast Guard or U.S. Customs authorities would be able to identify it by all the bullet holes in its side.

The spectacle of police officers as rumrunners raised the public’s interest and the importance attached to the case. The next morning, Olmstead, Clark, and their accomplices were charged with conspiracy to violate the Prohibition laws. Olmstead and Clark had their bail fixed at five thousand dollars, more than most men earned for two years’ honest work. Their case allowed Donald MacDonald to crow that the big bust marked only the start of Uncle Sam’s campaign to make Washington “Dry.”6 MacDonald told reporters those arrested were members of a major liquor ring operating throughout the Northwest.

Five days after the arrest, a grand jury indicted the members of the “police ring” on charges of conspiring to have and possess liquor; of conspiring to transport it by automobile; and of conspiring to transport, sell, deliver, and furnish it to unknown persons. The grand jury, and by extension the district attorney, did not ask for charges of smuggling, which would have required evidence of the ownership of the liquor.7 The conspirators’ attorney, Jack Sullivan, filed several objections, notably one claiming that the Eighteenth Amendment was unconstitutional, reminding the judge of a case pending before the Supreme Court, challenging the legality of the amendment.8

Just a few days before the next court date, Prohibition officers found the boat, the Jervis Island, that had brought the shipment to Olmstead and Clark.9 The capture of the boat emboldened MacDonald to repeat his earlier prediction that other surprising arrests would follow as the tentacles of the “alleged far-reaching Northwest booze-ring” were traced.10 In the meantime, Judge Neterer quickly dismissed Sullivan’s earlier objections, showing he would not treat bootleggers with a wink and a smile, a charge leveled at state and local courts, which seemed to prefer levying fines over trials and jail time.11 Clark and Olmstead would face the charges of conspiracy, which carried a two-year prison term and a fine not to exceed five thousand dollars, their coconspirators facing lesser charges because they had been employed. The trial was set for May.

Chapter 1

As the first weeks of the new decade passed in January 1920, Americans believed they understood the consequences as Prohibition descended upon the land, closing breweries, distilleries, and saloons. Even as bootleggers, rumrunners, and moonshiners—men like Roy Olmstead—stepped up to seize the opportunity, organizing themselves into conspiracies to obtain, manufacture, and sell liquor to willing buyers, few Americans imagined that the Eighteenth Amendment would not be a permanent fixture in their lives. Women activists, the foot soldiers who had won the battle to ratify the Eighteenth Amendment, were turning their attention to the impending ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment, giving women the vote nationwide. These twin amendments seemed to offer redemption, two chances to perfect the American soul, correcting the sins of the past and opening a new chapter for those women willing and able to face the challenges.

Pauline Sabin, a New York socialite, and Mabel Walker Wille-brandt, the U.S. assistant attorney general, would not have characterized themselves as redeemers, but they understood the impor- tance of the moment and the public perception that forever defined Prohibition as a women’s issue. Prohibition’s success or failure would be measured in the public’s consciousness, often, by the success or failure of these two women, whose paths would cross only a few times, but whose impacts must be weighed together. The political education they received during the Prohibition era represented American women’s struggle to capitalize on their newfound power, as voters and as standard-bearers for Prohibition, and defined the means by which other women could exert their influence. In the process, Sabin and Willebrandt absorbed lessons from the men they encountered, some of whom assisted their efforts, others resisting, and still others serving as touchstones for measuring advancement. One man, Roy Olmstead, the cop turned rumrunner, never met either woman, but his experience would help them define their beliefs about Prohibition, the limits of constitutional authority, and the rightness of their paths, reaching two very different conclusions.

* * *

• • •

Mrs. Charles Sabin stepped lightly through the gilded reception hall of the Hotel Astor, greeting national political figures, renowned business leaders, and members of New York’s highest society, each a prospect to be cultivated in a few brief moments, a daunting task as the rush of top hats and fur coats swept in. She was too polished not to look composed, at home, despite being required to balance different constituencies as on a knife’s sharp edge. The guests, including Mr. and Mrs. Cornelius Vanderbilt III and Mr. and Mrs. Theodore Roosevelt Jr., recognized Mrs. Sabin as one of their own by virtue of the political and business successes of her grandfather, father, uncle, and husband. Along with her fellow members of the recently created Republican Women of New York State, Mrs. Sabin welcomed as many guests as she could, directing them to the bar or the cloakroom, or helping them find their seats. The

women’s club had produced the event, in early December 1919, to raise money for the party’s campaign war chest and to inaugurate their organization with a grand splash at the hottest spot in Manhattan, in the French Renaissance Beaux Arts–style hotel built just for them: the wealthy, the powerful, and the famous.

The absence of the senior U.S. senator from New York, the powerful Republican James W. Wadsworth Jr., generated talk. Senator Wadsworth had sent a telegram, to be read from the podium, explaining why he could not attend, a cover story fooling no one. The antagonism between Wadsworth and club women was years old and well-known. The leaders of the Republican Women of New York State had declared war on Senator Wadsworth because of his opposition to women’s suffrage, even as the proposed Nineteenth Amendment neared full authorization by the requisite thirty-six states.1 Wadsworth further damaged his appeal by his opposition to the Eighteenth Amendment, weeks away from implementation, which had been carried to fruition by many of the same women supporting passage of the Nineteenth Amendment. Passage of the two amendments inspired “club” women to envision the next set of changes needed in government to improve society. Ousting Senator James Wadsworth seemed to many a logical step.

Like any apprentice activist at a key event, Pauline swung her head on a graceful swivel, offering a smile and a quick wave to Republican leaders, while keeping an eye out for members of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) and League of Women Voters (LWV),* people the hostess needed to greet and steer away from condemnations of Senator Wadsworth.* Criticism of New York’s senior Republican senator at a Republican fund-raiser, even one organized by a women’s group, would be vulgar, to Pauline’s way of thinking, and reflect poorly upon the group, endangering women’s relationship to the party. She intended to become a Republican Party insider, someone who sat in on the councils where policy was formulated. Like her mentor, Mrs. Arthur L. (Henrietta) Livermore, Pauline refused to be relegated to the shaky, hastily constructed “women’s divisions” being grafted onto the party apparatus.2 Her goal placed Pauline Sabin in a precarious position between the “club” women seeking to maintain a unified front and the male party leaders seeking loyalty to Republican candidates.

The Pacific

The Pacific Liberated Spirits

Liberated Spirits